About the Film * The Director * Screenings * Press * Talk Back * Educational Use

Overview The Story Background Epilogue Director’s Statement Credits

The families in Monkey Dance came to the United States from Cambodia, a small country in Southeast Asia. During a period of about six hundred years, between AD 802 and 1431, Cambodia’s mighty Angkor civilization built dozens of magnificent stone buildings, including the most famous, Angkor Wat. About four-fifths of Cambodia’s population lives in rural areas, many surviving as rice farmers. Traditional Cambodian, or Khmer, culture is very complex; it often emphasizes gracious hospitality, respect for elders, modesty, concern for community approval, and a desire to shelter young girls until they are married. Most Cambodians practice a form of folk Buddhism filled with personal rituals and public ceremonies.

During the age of classical imperialism in the 1890s, France dominated Southeast Asia and exploited it for its rubber and raw materials. With World War II came an attempt by the Japanese Empire to wrest economic and political control of the region, beginning a cycle of direct military violence that would last for forty years.

France attempted to reassert its domination in the years after the war. But after a catastrophic military defeat in Vietnam in 1954, the French began a complete withdrawal from all of Southeast Asia. Into this seeming power vacuum entered the United States, determined to keep the region from becoming a communist stronghold. Some historians argue that these years of U.S. military action brutalized the Cambodian people and in some way helped engender the horror that was to come.

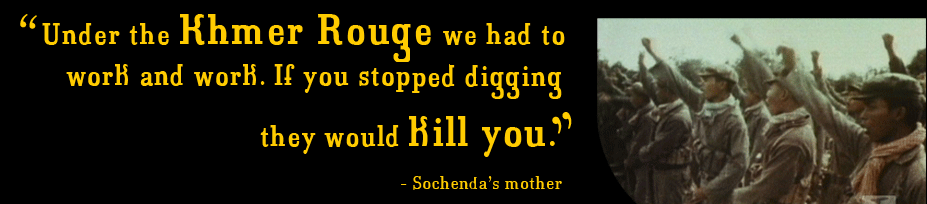

After the United States withdrew from Cambodia in the early 1970s, the Khmer Rouge, under the leadership of Pol Pot, took control of the country. The Khmer Rouge (“Red Khmers,” then formally known as the Communist Party of Kampuchea) established the state of Democratic Kampuchea in April 1975 and launched one of the most radical experiments in social engineering of the twentieth century. They aimed to create a classless utopian society – to erase two thousand years of Cambodian history and begin again at “Year Zero.”

The Khmer Rouge began by emptying all Cambodian cities of their population and sending residents to forced labor camps, where leaders maintained constant fear by feeding workers only a small amount of rice and killing those who did not work hard enough. Religion, schools, hospitals, banking, and private property were abolished. Traditional kinship systems were replaced with communal relationships.

Between 1975 and 1979, the Khmer Rouge tortured, interrogated, raped, and killed hundreds of thousands of innocent people. Some were executed en

masse in one of the infamous “killing fields” around the countryside. The Khmer Rouge specifically targeted educated people, artists, monks, urban dwellers, and anyone perceived as opposing the new regime. Approximately 90 percent of Cambodia’s traditional dancers — once a hallmark of Cambodian culture — were killed. Estimates on the total death toll during this period vary widely, but Western scholars calculate that 1.5 to 1.8 million people died from execution, disease, starvation, and overwork. This represents 20 to 25 percent of the total Cambodian population in 1975.

The carnage did not end until neighboring Vietnam, now united under Communist rule, invaded Cambodia to dislodge Pol Pot. Cambodia still struggles to overcome its dark history and the legacy of poverty, corruption, and millions of leftover land mines.

During the Khmer Rouge reign of terror, refugees streamed into vast refugee camps in neighboring Thailand. With the hopes of preserving their culture amidst the turmoil, surviving dancers pieced together the remants of traditional dances they knew and taught them to fellow refugees (including Tim Chan Thou, founder of the Angkor Dance Troupe). The United States, tacitly acknowledging its own role in destabilizing Cambodia, accepted thousands of refugees in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Primary relocation sites were set mostly along the West Coast of the United States. Secondary resettlement sites were designated across the country, including Lowell, Massachusetts – a historic mill city that has seen waves of immigrants who have supported its industries.

Most Cambodian refugees arrived in America speaking almost no English, knowing little of American culture, and having few job skills applicable to modern society. After 10-25 years in America, many of these families are still struggling to make ends meet, with parents working multiple low-wage jobs in factories or service industries. They do their best to preserve their culture by speaking Khmer at home, cooking Cambodian food, attending Buddhist temple regularly, and living according to their traditions.

Their children, though, are growing up in a multicultural society, where English is their language of choice and American pop culture their natural habitat. Cambodian parents are often shocked by their children’s choice of hairstyle, clothing, music, or friends.

Many Cambodian-American teens fall prey to gang membership, drug use, teen pregnancy, or domestic violence. Several of Linda’s, Sochenda’s, and Samnang’s older siblings were drawn into these problems. What makes these three teens special is both their determination to avoid these pitfalls and their dedication to a centuries-old dance tradition that helps them find success on their own terms.